The International Journal Of Engineering And Science (IJES)

|| Volume || 4 || Issue || 6 || Pages || PP.51-57 || June – 2015 ||

ISSN (e): 2319 – 1813 ISSN (p): 2319 – 1805

www.theijes.com The IJES Page 51

Why a Community Tolerates Dust Pollution and Noise Disturbance? A Study on Corporate Social Responsibility in Nickel Mining

Herianto Mustafa1

1School of Social Development, The Philippine Women’s University, Manila, Philippines

Andi Ilham Samanlangi2, Muhammad Idrus3, Emiliano T. Hudtohan4, and Sanihu Munir5

2Dean, College of Engineering, University of Pejuang, Makassar, Indonesia 3Director, Mandala Waluya, Institute of Health Sciences, Kendari, Indonesia 4Graduate School, De La Salle Araneta University, Metro Manila, Philippines 5Graduate Study, Tri Mandiri Sakti, Institute of Health Sciences, Bengkulu, Indonesia.

—————–ABSTRACT—————-

The purpose of this paper is to present the findings of a research on Why a Community Tolerate Dust Pollution and Noise Disturbance? A Study of Corporate Social Responsibility in Nickel Mining

The study was conducted in the village of Motui, Sub-District of Motui, District of North Konawe, Indonesia. Eighty samples were randomly selected using Slovin’s formula from 352 population affected by the mining operation. The research methodology applied a descriptive analysis. The measurement of study variables used Likert scale (Riduwan, 2003), namely: strongly agree (score 5), agree (score 4), neutral (score 3), disagree (score 2), and strongly disagree (score 1). In valuing empirically the research variables, this study adopted the valuing principle of Arikunto (1998). An in-depth analysis was conducted using interviews, discussions and observations to validate the response of respondents.

The findings showed that 1) based on the total average of the perception of the members of the community, mining operation is categorized as average or neutral (2.75). It means the presence of the mining company and its operation did not significantly disturb the surrounding community. In addition, based on personal communication through interviews, monetary compensation mitigated their intolerance to the noise disturbance and dust pollution. 2) With regard to the CSR of the mining companies,

the survey indicated community members are strongly dependent on the on decisions of mining companies and the local government. It means they are passive recipients and beneficiaries. These two items showed the weak bargaining position of community towards their fate. It is evident that their need for cash money is more much preferred in exchange for expressing and demanding for their rights. In summary, the perception and attitude of the respondents showed a high average score of 3.99 in terms of community participation in CSR of the mining companies.

KEYWORDS: Corporate social responsibility, environmental pollution, nickel mining, community participation

——- Date of Submission: 18 June 2015 Date of Publication: 5 July 2015 ——–

I. INTRODUCTION

Based on the observation of the researcher on the mining company in their exploitation process, there are various problems between the community and the mining activities of companies. Rallies and protests of the communities and NGO’s happen nearly in every mining site. Why a Community Tolerates Dust Pollution and Noise… www.theijes.com The IJES Page 52

Makati and Rahim, (2013), a representative of the community of the Sub-District of Motui, accused the mining company in Motui of polluting and degrading natural environment with their mining activities. Susyanti Kamil (2013), mentioned that a number of mining companies have violated the mining permit issued by Chief District of North Konawe by expanding their operation into protected forest. Kamil suspected that the local government of North Konawe played an important role in the deterioration of the forest by issuing the mining permit within the protected forest. It seemed that instead of improving the welfare of the community, the people in North Konawe are haunted by the tremendous damage done by the mining companies to their environment. What then is the meaning of corporate social responsibility (CSR) of the mining companies if it merely a piece of candy given as a dole out in exchange of the huge economic loss to present and future generation.

Southeast Sulawesi Wahana of Environment (WALHI) and North Konawe People Coalition for Justice (KRAKEN) on December 14, 2013 accused Aswad Sulaiman, Chief District of North Konawe as a master mind of the deterioration of the district forest. Hence, the NGOs conducted a rally at the District Office of Forestry and Natural Resources Conservation Board (BKSDA). Their accusation was based on the number of mining permits included the area of protected forest. BKSDA in its dialogue with the demonstrators admitted that 28 nickel mining companies in Southeast Sulawesi have mining operations in these protected forests (Media Sultra, 2013).

When the researcher visited Motui, he found out that the environment was polluted by dust and sludge from the excavation and transportation of nickel ore from mining site to stockpile areas and from the shipment activities. Nickel ore transportation also disturbed people the peace and quiet of community with the noise from heavy trucks along the road and during the shipment activities.

However, based on researcher’s observation in Motui, the community were passive and they did not pay attention their discomfort and they did not participate in any rally against the mining companies or the local government when, in fact, the rapid environmental degradation directly affected the community welfare.

Indonesian Act Number 32, issued 2004 on local government autonomy explains that the implementation of regional autonomy aims to improve the quality of public services and the welfare of the community, creating efficient and effective of human resource management, as well as empowering and creating a space for people to participate actively in the process economic development.

Those who conducted rally against the mining companies and the local government of North Konawe were not from the community from around the mining site, but they were NGOs from the district and provincial level who aired their concern on the deterioration of environment in North Konawe, particularly in Motui. However, in another study, Harun (2012) mentioned that the people in the Sub-District of Routa, District of Konawe, adjacent to the District of North Konawe, showed their satisfaction towards the presence of PT Bintang Delapan Wahana Nickel Mining Company (PT BDW NMC) in their exploration process for nickel mining operation in Routa.

This phenomenon drove the researcher to conduct a study to answer, why the affected community tolerates dust pollution and noise disturbance from nickel mining activities in the context of corporate social responsibility of the mining company.

The mining company did not pay much attention to address the environmental pollution problem in Motui since community was satisfied with the agreement with the mining company. Malen Baker (2008) explains the tendency that business leaders don’t waste time with this “stuff”, because the mining company is focused on the core of its business which is profitability. Therefore, the implementation of corporate social responsibility is passed on as responsibility of the politicians and local government.

Garvey and Newell (2005), who observed the weaknesses of CSR, proposed a new approach to improve CSR through a concept of corporate accountability (CA) or corporate social accountability (CSA). They pointed out the limitation of the CSR where the policy directed form above rather than aspired from below. It also overlooked the strategies that can be employed by the powerful to control the agenda and frame the issues in ways that deny spaces for opposition.

Porter and Kramer (2011) argue that innovating to meet society’s need and building a profitable enterprise are the twin goals of the next generation of competitive companies doing corporate social responsibility. Pfitzer, Bockstette and Stamp (2013) following Porter and Kramer’s idea of creating shared value with and for their external stakeholders worked on a model that encompasses the creation of a social and business value which includes: social purpose, a defined need, measurement, the right innovation structure, and a co-creation.

Hess, Rogovsky, and Dunfee (2002) envisioned the next wave of corporate community involvement as corporate social Initiatives (CSI), where corporations are performing CSR from the perspective of the community where there is active participation in sustainable social enterprise. Habaradas (2012) reported that there is empirical evidence that a company’s philanthropic CSR activities would later legitimize its presence in communities through sustainable programs. Why a Community Tolerates Dust Pollution and Noise… www.theijes.com The IJES Page 53

Hudtohan (2014) pushed the CSR concept from the perspective of community development, proposing the models of Cura (1886) organization development in community, Buenviaje (2005) community organization, and Netario Cruz (2014) social optimum development quadrant of sustainability.

II. LITERATURE REVIEW

The term “community participation”, according to Nick Wates (2000) refers community, as a group of people sharing common interests and living within a geographically defined area. Another author explained the community as a group of people who come together to achieve a common objective, even if they have certain differences (Hamdi, 1997). Furthermore, Wates defined participation as “the act of being involved in something”.

Involvement of community according to Samuel Paul (1999) is community participation which refers to an active process whereby beneficiaries influence the direction and execution of development projects rather than merely receive a share of project benefits.

The tolerance of the community towards dust pollution and noise disturbance in this study shows their powerlessness in bargaining their position and interest to influence the direction and execution of development projects like CSR; the take a passive stance and become mere recipients of project benefits that are often unsustainable philanthropic gestures.

From a wider perspective, Nicanor Perlas (2000) proposed a tri-partite partnership consisting of three sectors namely civil society, business and the government in his book, Shaping Globalization, to work together for a common purpose and achieve greater human goals for all parties concerned. The defeat of the WTO in Seattle shows that a third global force has emerged with elemental strength to contest the monopoly of world economic and political leaders over the fate of the earth. This third force is what we now know as global civil society.

The tri-partite partnership members in this study consist of civil society in the Sub-District of Motui as a first sector, Bumi Konawe Abadi Nickel Mining Company as a second sector and Local Government of North Konawe as a third sector. The civil society in the Sub-District of Motui needs to be empowered as a community vis-à-vis the mining companies and the local government. However, this community spirit is not yet felt by those who live in Motui. They are poorly educated; the community is not organized and they need to assert their rights and be empowered to make a choice to protect their interest as citizens and members of civil society. Because of their lack of self-initiative and much more community initiative, most of the time, they are directed and dictated by the local government and the mining company to receive whatever the philanthropic dole out that falls on their lap.

Up until 1961, Milton Friedman insisted that a corporation is “an artificial person and in this sense may have artificial responsibilities, but business as a whole cannot be said to have responsibilities.” He concluded that businessmen who subscribe to corporate social responsibility (CSR) are practicing “pure and unadulterated socialism” and that they are “undermining the basis of a free society.” (Friedman, 1970).

Since the time of Joel Bakan (2004), corporate responsibility has becomes a new creed for a self-conscious corrective measure to the profit-oriented visions of the corporation. Bakan as a corporate activist speaks with impunity about the sins of the corporation in his book, The Corporation. Mineral extraction corporations, in particular, have the power and resources in alleviating poverty in the area where they operate. Their commanding presence has the potential to grab the new opportunity to serve the impoverished through corporate social responsibility initiatives. Present conditions as felt by the people in Motui such as poverty, poor standard of living, lack of education and oppressive living conditions are social circumstances which have been predicted by Coleman (2011).

Caroll’s (1999) CSR is expressed in the now classical pyramid of corporate social responsibility. In this Pyramid a corporation has four types of responsibilities. At the bottom of the pyramid is most obvious of the economic responsibility of the company to be profitable. The second layer of the pyramid is legal responsibility to obey the law. Business must obey the laws and follow industry norms. It means to put social codes before any other social responsibilities are pursued. The third layer in corporate social responsibility is ethical responsibility to do what is good, just and fair in addressing business’s ethical responsibility, and at the top of the pyramid is the philanthropic responsibility to contribute resources to community to improve quality of life, how businesses can positively contribute to the overall quality of life (Hennigfeld et al 2006). Why a Community Tolerates Dust Pollution and Noise… www.theijes.com The IJES Page 54

Basically, the CSR of the mining company must have two sacred missions: first, the welfare of the society and second. the preservation of the environment. Therefore, it is a duty of every corporate body to protect the interest of the society at large, and it should take initiative to perform its activities within the framework of environmental norms specified by the government and mandated by cultural and religious prescriptions

Holme and Watts (2000) view CSR as “the continuing commitment by business to behave ethically and contribute to economic development while improving the quality of life of the workforce and their families as well as of the local community and society at large”

The review of related literature on CSR cited in this study points to a most critical perspective that every mining company Motui has the social responsibility to address the community needs that are directly affected by their operations. Subsequently, by invoking the tripartite principle, the mining company, the local government and the community of Motui have to come together and work for a common good that benefits all.

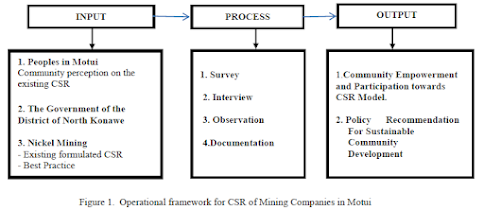

III. OPERATIONAL MODEL

The operational model of the study in Figure 1 shows the system flow of input, process and output of tripartite sectors: the people of Motui, the Nickel Mining Company and the Local Government of North Konawe.. The integrated tri-partite relationship of the community with the mining company and the local government is intended to build community empowerment so that there is active participation in creating a CSR Model and policy recommendation for sustainable community development coming from the community.

IV. METHODOLOGY

The respondent population in this study was the community in the Village of Motui, affected by nickel mining operations and activities. They were 352 community members affected by mining operations out of 585 total population of the Village of Motui. The sampling technique used in this study was simple random sampling.. To determine the sample size in this study, Slovin formula was applied. From a population of 352 a sample size of 78 was arrived at. Researcher made it 80 in anticipation of drop-out or incomplete data. All eighty respondents were actively participated in filling-up questionnaires. Interview and group discussions were conducted to triangulate survey data.

Data was analyzed using descriptive statistics to illustrate and provide an empirical description to answer the research questions (Ferdinand, 2006). The measurement of variables was conducted using Likert scale (Riduwan, 2003), namely: strongly agree: 5 points, agree 4 points, neutral: 3 points, disagree: 2 poits, and strongly disagree: 1 point (Allen 2007). The mean values were classified in the score category scale. The mean scale range was divided into five interpretations/categories: very low, low, average, high and very high (Arikunto, 1998). In-depth analysis was conducted using interview, group discussion and observation to explore the meaning of their choices and ideas. Why a Community Tolerates Dust Pollution and Noise… www.theijes.com The IJES Page 55

V. ANALYSIS AND RESULT

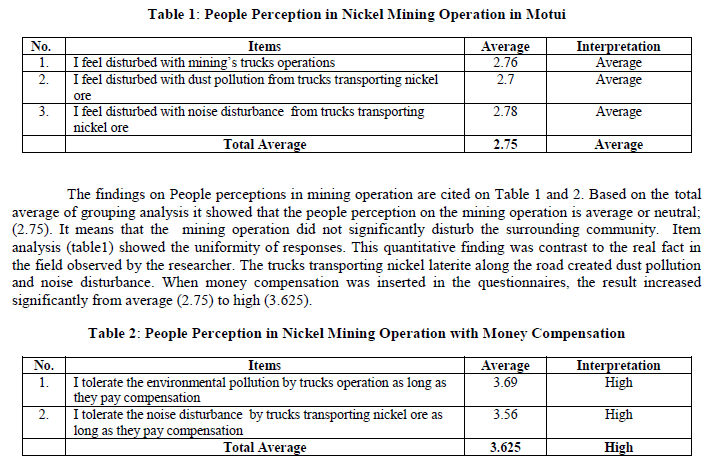

There were two analyses in this study: first, group analysis and second, item analysis. The group analysis falls under the heading of People Perception in Nickel Mining Operation in Motui. This group consists of item no. 1). general disturbance with the existence of the mining activities, 2) noise disturbance from the trucks transporting nickel ore from mining site to stockyards or shipments, 3) dust pollution from the same activities, 4) noise disturbance with money compensation and 5) dust pollution with money compensation

In-depth interviews were conducted among the respondents who supported money compensation. Their reasons for tolerating dust pollution and noise disturbance was that 1) the compensation amount as much as Rp. 250.000 or equal to USD 20 was meaningful as additional fund for their daily expenses. 2) They were afraid, if they protest, the money compensation might be cut off. 3) They also were afraid that the mining company might transfer to other place and there will be no more money compensation. These weaknesses are well demonstrated in Table 2 where a;; the responses are high.

Second group analysis shown in Table 3 falls under the heading of Community Participation in CSR of the Mining Company. This group consists of item no. 1) The mining company determines the kind and amount of their CSR, 2) Mining company and the local government are in the position to determine the kind and the amount of CSR based on their significant educational background, and 3) The payment of CSR in cash to the community is proper because people need money.

Table 3: Community Participation in CSR of the Mining Company

Community Participation in CSR, particularly item no 1 and 2 showed a strong indication of people dependency on mining company and local government decisions. These two items showed the weak bargaining position of community towards their own fate. It is also shows their need for cash money over their right to express themselves regarding the mining activities. The total average score of 1.1 is interpreted as very low. It means the community does not desire participation and they are willing to be passive receivers of cash money and forego their personal rights to express themselves.

VI. CONCLUSION

Based on the findings and analysis of the result, the following conclusions were derived. The mining trucks transporting nickel laterites from excavation sites to stockyards and shipment location did not significantly disturb the community who live along the road. In this study, the researchers found out two groups of peoples, 1) those who were disturbed with the trucks activities because they stay along the road-side, and 2) those who tolerate the disturbance from the trucks activities because they stay far from the road-side. However, when money compensation was mentioned in the questionnaires, those who stay along the road-side changed their choice from not tolerate to tolerate.

From this pictures, it can be concluded that the poverty problem exists in Motui, where money compensation of Rp 250,000 or equal to USD 20 per household had forced them to sacrifice their tranquility and health. It can be concluded that people are highly dependent for monetary benefits and are at the mercy from mining company and local government. It means, people in Motui have a weak bargaining power against mining company regarding the kind of CSR activity intended for their community. This powerless and weak bargaining position of the community showed that the local government ignored their duty and failed in their initiative to empower the community through community organizing and poverty alleviation program.

VII. RESEARCH LIMITATION AND FUTURE STUDY

The major limitations of this study revolve around the limited variables that influenced community tolerance towards environmental pollution and noise disturbance, to reveal the broader understanding in the interaction among variables. The limited population and sample was limited to Motoui. Some research assistants were not able to avoid the temptation to influence the respondents because they were not fully literate and familiar with role of local government as well as nickel mining company’s policies regarding the concept of social responsibility.

For the future study, the researchers should focus on community organizing and empowerment as a further step in the involvement and fully participation of the community in corporate social initiative rather than merely corporate social responsibility. In addition, the further research should also intensify in-depth interview, discussion and observation to reveal broader understanding and variety of ideas in enriching the results. Instead of quantitative method, other methods like action research and ethnographic study may be conducted for experiential approach to understanding the mining issues regarding corporate social responsibility and corporate social initiatives.

REFERENCES [1] Alfonso,F.. & Amacanin M, 2007. Strategic Implication for CSR: Framing the Corporate Strategy in Doing Good in Business Matters: CSR in the Philippines Framework, Manila: AIM and De La Salle, GSB, [2] Allen, Elain I. Christopher A. Seaman.. 2007. Likert Scales and Data Analyses, New York:

http://asq.org/quality- progress/2007/07/statistics/likert-scales-and-data-analyses.html. [3] Badan Pusat Statistik (BPS), 2012. Konawe Utara Dalam Angka Tahun Kabupaten Konawe Utara..

[4] Baker, Malen, 2004. Corporate Social Responsibility – What does it means? http://www.mallenbaker.net/csr/definition.php, June 2004. [5] Bleckley, David, 2008. Assessing Participatory Development Processes Through Knowledge Building, SPNA Review, Volume 4/Issue 1, Article 3, .2008 http://scholarworks.gvsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1001&context=spnareview [6] Brucksch, Susanne and Carolina Grünschloß, From Environmental Accountability to Corporate Social Responsibility? Reflections on the CSR Boom in Japan from the Perspective of Business Management and Civil Society Groups [7] Buenviaje, Orlando. (2005). The heart of community organizing. [8] Carroll, Archie B. (1999), Corporate Social Responsibility. Business and Society. 38, 3.

[9] Coleman, Emily A.. 2011. An Evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility Initiatives Implemented by Alcoa,Votorantim, and Vale as a Means to Aid in Poverty Alleviation in the Brazilian Regions These Mining Companies Operate, CMC Senior Theses. Paper 198. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/198, [10] Cura, Nenita. (1986). The Role of Organization Development Involving a Model of Social Liberation Amongst the Fishermen in Rizal. A doctoral dissertation, Asian Social Institute, Manila. [11] Garriga, E & Mele, D, 2004. Corporate Social Responsibility Theories: Mapping the Territory, Journal of Business Ethics, . [12] Garvey, Niamh and Peter Newell, 2005. Corporate accountability to the poor? Assessing the effectiveness of community-based strategies, Development in Practice, Volume 15, Numbers 3 & 4, June 2005. [13] Harun, A. Azis, 2012. The Tripartite Role Of Government, Business, And Civil Society In Promoting Good Mining Management In The Sub-District Of Routa, Konawe, Indonesia: A Dissertation, Manila: The Philippine Women’s University, [14] Hess, Davis, Nikolai Rogovsky, Thomas W. Dunfee. 2002. The Next Wave of Corporate Community Involvement:Corporate Social Initiatives, California Management Review Vol. 44,No. 2 Winter 2002 Why a Community Tolerates Dust Pollution and Noise… www.theijes.com The IJES Page 57

[15] Habaradas, Raymund. September 2012. Shifting Philanthropic Motives: Shell’s Corporate Social Initiatives in the Philippines. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3, 17. [16] Hess. D., Rogovsky, N., and Dunfee, T.W. 2002. The Next Wave of Corporate Community Involvement: Corporate Social Initiatives. California Management ReviIew. 44, 2. [17] Hudtohan, Emiliano T. 2014. Threefolding and Corporate Social Initiative, Manila: De La Salle University,. [18] Jogiyanto. 2011. Pedoman Survei Kuesioner: Pengembangan Kuesioner, Mengtasi Bias dan Meningkatkan Respon, Yogyakarta: Universitas Gajah Mada,. [19] Kahn, Si., 2010. 20 Principles for Successful Community Organizing http://www.alternet.org/story/145924/20_principles_for_successful_community_organizing [20] Mencias, Christina F.. 1991. Designing Questionnaires, National Teacher Training Center for the Health Professions, Manila: University of the Philippines Manila. [21] Netario-Cruz, May Jean. n.d. Social optimum development: Quadrant of Sustainability. http://sodqos.weebly.com/contact-us.html [22] Pfitzer, M., Bockstette, V. and Stamp, M. September 2013. Innovating for Shared Value. Harvard Business Review. [23] Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. 2011. Creating shared value. Harvard Business Review, 89. 1. [24] Riduwan, DR.M.B.A., 2003. Dasar-Dasar Statistika. Bandung: Penerbit Alfabeta, , [25] Pujiraharjo, Widodo I.. 2013. Qualitative Research Methods, Surabaya: Airlangga University..

[26] Roy, Syaita.. ,2013. Corporate Shared Value: The New Competitive Advantage, California: http://www.triplepundit.com/2013/01/corporate-shared-value-new-competitive-advantage/

[27] Spector, B, 2008. Business Responsibilities in a Divided World: The cold war roots of the Corporate Social Responsibility Movement. Enterprise and Society. [28] Saleng, Abrar. 2004. .Hukum Pertambangan.Yogyakarta : UI Press. [29] Tsoi J.), 2010. Stakeholders Perceptions and Future Scenarios to Improve Corporate Social Responsibility in Hong Kong and Mainland China, Journal of Business Ethics. [30] Republika Daily. 2014, CSR Fund in the Election Year, Jakarta, January 15, 2014. [31] Kendari Pos Daily. 2013, Nickel Mining Companies Destroy Protected Forest, Kendari, December 23, 2013 [32] Media Sultra Daily. 2013, Chief District Involves in the Deterioration of Protected Forest, Kendari, December 15, 2013.