Elements of Spiritually-driven Management in a Catholic Business School: a literature review

Dr. Emiliano T. Hudtohan, EdD

San Beda College Graduate School Research and Development Journal

October 2015

Based on a review of related literature on spirituality and religiosity in general and at the workplace in particular, three spiritualities emerged: Maharlikhan spirituality, devotional spirituality, and global spirituality. The convergence of the three spiritualities resulted to: folk spirituality, social-activist spirituality, and personalist non-denominational spirituality. These six variants are suggested as elements of a spirituality-driven management framework at an academic workplace. The study made use of heuristic research in presenting the researcher’s personal spiritual insights culled from his experience with Lasallian educational management for almost six decades as student, administrator and faculty. The framework for a spiritually-driven management was traced from Lasallian humanistic education to social-activism; a review on the history of spirituality in general and spirituality and religiosity at the workplace in particular contributed to the concept of a spiritually-driven management. This study reviewed in retrospect the development of Lasallian business-liberal education in creating a prospect for a spiritually-driven management framework.

Key words: spirituality, theology, humanistic education, management, social formation, social teachings, vortex and babaylans.

Introduction

The rise of spirituality as context in the workplace is a signal that humanistic management, which is a reaction against a materialistic business worldview, has progressed towards a value-based and faith-based management. Spiritually-driven management has been practiced as purpose driven leadership and meaningfulness of work. It is extensively discussed in empirical studies as spirituality in the workplace (SW) and spirituality and religiosity in the workplace (SRW). This paper is a sequel to an earlier article, Spirituality in the Workplace: Quo Vadis? (Hudtohan, 2014).

Historically, humanistic management came about as a reaction to an extreme pursuit for wealth through bottom line profit, characterized by business in the industrial revolution period. It was the Marxist-socialist movement that mirrored the ‘inhumanity’ of business. It was the social doctrine of the Catholic Church that declared and continues to uphold ‘human’ dignity of the workforce, operationally responsible for business products and services and bottom line profit.

But Marxist-socialists and capitalists continue to debate on a materialistic business management platform. On the other hand, the Catholic Church continues to espouse the dignity of the human person in business. The idea that key players in business are spiritual beings seems to be anathema to many. On the contrary, I believe that the problem of business management is spiritual. And from a macro perspective, I join Walsch’s (2014) observation that “The problem of humanity today is a spiritual problem.”

Objectives

The primary purpose of this paper is to develop the elements of a conceptual framework for a spiritually-driven management in a Catholic business school. It seeks to review the historical roots of spiritual activism at De La Salle University that resulted to its current social activism. It revisits the pre-Spanish Maharlikhan spirituality intended to culturally anchor the concept of a spiritually-driven management. Lastly, it seeks to demonstrate the use of heuristics, historiography and storytelling as research tools in arriving at the concept of spiritually-driven management.

Significance of the review

First, this review challenges the faculty, students and administrators, who are attached to their respective institutional spirituality, to have a panoramic view of other spiritualities. A new spiritual perspective opens a worldview that is needed in a global academic and business environment. Second, academic decision-makers who wish to innovate may use the spiritually-driven management framework as platform for enhancing business curricular and co-curricular programs. Third, the spiritually-driven framework may be used to establish empirical data on the six spirituality variables in studying management and spirituality programs in a Catholic business school

Methodology

I made use of heuristic research, historical research and storytelling in narrating and exploring the concepts related to spiritually-driven management.

Heuristic research attempts to discover the nature and meaning of phenomenon through internal self-search, exploration, and discovery (Moustakas & Douglass, 1985). As an axiologist, I explored my corporate and academic experience, which ultimately led me to further explore spiritually in the workplace (Hudtohan, 2014) as driver of management practice. It helped me discover the nature and meaning of spirituality in the context of business management.

The historiography (Bloch, 1962) provides a retrospect-prospect perspective (Gonzales & Tirol, 1984; Hudtohan, 2005) on spirituality. A historical review of related literature on spirituality in the workplace (SW) and spirituality and religiosity in the workplace (SRW) by Geigel (2012 and Karakas (2010) showed empirical support in conceptualizing a spiritually-driven management framework.

Storytelling (Pillans, 2014; Brown, 2012) gets a personal message across and helps the reader’s “internal perspective and in cases where choices are unconscious, it can provide a new viewpoint that is more conscious” (Simons, 2001). Samuels and Lane (2003) assert that “Restorying reality is…changing a person’s belief system and instilling hope and spirit.” In restorying a spiritually-driven management, I experienced catharsis in articulating my views on spiritual issues.

This is a qualitative research; it integrates my experience as an axiologist immersed in business ethics and social responsibility in the graduate school of business. A heuristic-historical approach allowed me to narrate my spiritual viewpoint as experienced in the academic and corporate environment for almost 5 decades.

Related Literature on Humanistic Education and Social Activism

Christian education

I traced the humanistic education at DLSU through my experience as guidance counselor of the grade school department in 1976 before it was transferred to De La Salle Zobel, Ayala, Alabang. Had the university retained the grade school and high school departments at its Taft campus and had there been a vertical academic integration in the 70s, the implementation of K-12 would have been less cumbersome for DLSU. The evolution of Lasallian devotional-activism to humanistic social-activism could have been also vertically integrated. For almost four decades, spiritual-activism (1941-1983) at De La Salle University (DLSU) was driven by the Baltimore catechism and the Confraternity of Christian Doctrine that addressed personal holiness and sanctification. By 1983, the university entered into a phase of social activism. It was driven by Lasallian concern for the poor, a calling of the Philippine Church to give preferential option for the poor and the Roman Catholic Church’s call for social justice.

In transition, the social concern of the university may have soft-pedaled the need for devotional spiritual practices that anchor the social activist to a personal religious experience while being of service society. Personal spiritual development remains the foundational core of social responsibility and corporate social responsibility in the 21st century.

Historically, the school of business of DLSU came almost a decade after it was founded in 1911. Maison du De La Salle became De La Salle College when it was incorporated in 1912 and it served as residencia of the Brothers’ Community and student boarders and escuela for Filipino boys. Administratively, the director of the Brothers Community was primarily responsible for both the spiritual life of the Brothers, the students and the faculty. Fundamentally, the spiritual leadership was in the hands of the director who managed both the Brothers and the school.

In 1920, it offered a two-year commercial course, five years ahead of the courses in humanities. For this reason, DLSU has been identified primarily a business school. In 1925 it offered courses for an Associate in Art, Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts. In 1930, the college was authorized to confer the degrees of Bachelor of Science in Education and Master of Science in Education. These non-business courses are balancing the business interest of the middle class with classical education in liberal arts. By 1961, it offered a five-year double degree: Liberal Arts-Commerce and Liberal Arts-Education. Since then, a humanistic education was enshrined. St. Irenaeus (185 AD) said, “Man fully alive is the glory of God.” And St. John Baptist De La Salle on the feast of St. Andrew, the apostle, affirmed St. Irenaeus when he said, “It is in the company of Jesus that you work for the glory of God” (Meditations, 78, 2).

When the nine pioneering Christian Brothers arrived in the Philippines in 1911, they had “a clear understanding of their primary mission…To give a Christian education to boys.” (Baldwin, 1982) The mission “to give Christian education to boys” cited in the Bull of Approbation of Pope Benedict XIII in 1724 specified that the Brothers “should make it their chief care to teach…those things that pertain to a good and Christian life… they chiefly imbue their minds with the precepts of Christianity and the Gospel” (Common Rules and Constitution).

Humanistic religious education

In the 70s, Banayad and Carillo of the Institute of Catechetics in Manila developed the human evocative approach (HEA) to catechism. The approach was learner-centered and experiential, significantly veering away from the kerygmatic, Gospel-centered catechism. It was gleaned from the conferences in Bangkok (1962), Katigondo (1964), Manila (1967) and Medellin (1968) which advocated an experiential learning anchored to an anthropocentric theology (Clarke, 1970; Ordoñez, 1970; Erdozain, 1970; Moran, 1967).

The grade schools of De La Salle-Manila and La Salle Green Hills became the breeding ground for the human evocative approach (HEA) in teaching religion (Caluag, 1972; Carillo, 1976; Hudtohan, 1972, 1976; Surratos, 1988). Fallarme (1983) noted that the social sciences shared similar HEA techniques in helping the learners relate with others at Philippine Women’s University-Jose Abad Santos Memorial School.

Hudtohan (1972) suggested using HEA as basis for integration of religion class and guidance at De La Salle Grade School. This is supported by Erikson’s (1968) epigenetic principle of personality development and spirituality indicates that each stage of human development is part and parcel of spiritual development. Fowler’s (1981) stages of faith show how the spiritual life of an individual grows over a period of time until a universal faith is attained upon maturity. Caluag (1980) assessed the humanization and Christianization in five De La Salle schools in the Philippines and concluded that the spiritual needs of the youth be addressed.

Endaya, Br. Andelino Manual Castillo FSC Education Foundation (BAMCREF) director (1983-1996), introduced the catechists to HEA teaching catechism in the public schools. In 1997, a new catechism, Modyul sa Katisismo at Kagandahang Asal series aligned with HEA was published under guidance of Br. Andrew Gonzalez, FSC and Director Louie Lacson. A humanistic religious education has found its way into the public school classrooms through professional Bamcref catechists. By this time, spiritual formation has been humanized through the HEA.

Social Formation

In 1983, the Center for Social Concern and Action (COSCA) was established by Br. Andrew Gonzalez, FSC and Juan Miquel Luz to make Lasallian education relevant and responsive to the needs of Philippine society and prepare its students to become socially responsible. This started a new era of institutionalized social-activism; it eventually eroded the spiritual-activism that focused on catechetical evangelization through Sodality of Mary members, student catechists, and professional catechists. In 1952 the student catechists in public schools were replaced by the Bamcref professional catechists. But by 2014, more than six decades later, all the professional catechists were permanently retired.

The shift from evangelization to community involvement was based on a realization that the existential need of the poor is not spiritual. This movement is supported by liberation theology (Gutierrez, 1973) that influenced many Catholic institutions to focus on social action for and social justice among the oppressed. Significantly, after Vatican Council II, a shift from theocentric to anthropocentric theology expressed humanistic maxims like: Christianity peaks in the fullness of being truly human (Schleck, 1968). This shift veered away the focus of Catholic Action (CA), which made the laity a ministerial extension of the clergy for: 1. evangelization, 2. formation of Christians, 3. spiritual renewal through piety and action, 4. defense of the Catholic faith and Christian morality, and 5. spreading of Christ’s kingdom and the common good of society (PCM II: 1997).

The CA stampita prescribed a devotional spirituality; members declared that: “It is my primary duty to strive for personal holiness. To accomplish this: I shall hear Mass daily if possible; pray the rosary daily; receive the sacraments at least once a week; make frequent visits to the Blessed Sacrament; spend at least 15 minutes a day for spiritual reading and meditation; and every year attend spiritual retreat and periodic recollection” (Hernandez, c1960).

In 1994, the DLSU mission statement declared that it considered itself a dynamic resource of the Church and Nation involved in the process of national transformation. The social activism of the university was in “solidarity with the poor.” In 2001, its vision-mission it strengthened its social responsibility by creating “new knowledge for human development and social transformation” and “building a just, peaceful, stable and progressive Filipino nation.” (DLSU, 2003).

While it updated the original religio, mores, and cultura values of the 1911 founding Brothers within the framework of human and social development, this shift may have been detrimental to the religious, and more so the spiritual, aspect of personal development of the students and faculty.

Historically, the service learning under COSCA has its roots from two Lasalian organizations: The De La Salle Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary and the Student Catholic Action. On June 28, 1941 De La Salle College Br. Flannan Paul, FSC met with the members of Sodality of the Blessed Virgin Mary to prepare them to teach catechism in a public school in Fort McKinley (Hudtohan, 2005).

By 2011, the DLSU Community Engagement (CE) conceptual framework of COSCA advocated (a) active collaboration (b) that builds on the resources, skills, and expertise, and knowledge of the campus and community (c) to improve the quality of life in communities (d) in a manner that is consistent with the campus mission. (AUN, 2011)

The CE Framework became a guide for all Lasallians to anchor themselves to the overall DLSU vision and mission in dealing with the current social realities, using a preferential option for the poor lens. It follows a progression cycle from awareness and partnership building to actual community engagement, leading towards personal and societal change; it envisions a socially aware and active Lasallians; it works for empowered, sustainable, and disaster resilient communities (Primer on the DLSU CE Framework, 2011).

Tupas (2012), in addition to COSCA’s social engagement framework, included Vickers, McCarthy and Harris (2004) service learning framework, Brown and Keast (2003) citizen-government engagement and Stevenson and Choung (2010) TQM for the DLSU Ramon V. del Rosario College of Business social paradigm. He enumerated the various curricular subjects in business as content for service learning. The courses on Lasallian leadership, business ethics and social responsibility are being aligned with social activism through community engagement. Service learning (Hudtohan, 2013; 2014) as co-curricular program in coordination with COSCA is a major shift from the DLSU spiritual activism in the 60s.

However, the social focus of service learning has somehow lessened the personal relationship between the faculty and students in terms of coaching and mentoring them as they journey not only in social service engagements but more importantly in their spiritual formation. Lost in transition amidst the whirlwind of activities is time for personal reflection after community engagement. By sheer number of 40 plus students under one faculty member, the reflection paper is not enough and the one-time community engagement is not enough either. I am proposing a spiritually-driven management to address a sustainable spiritual development.

Related Literature on Spirituality

Challenge to Catholic Business Institutions

At the De La Salle University (DLSU) Management and Organization Department (MOD), I saw a need to move forward its humanistic management thrust to that of a spiritually-driven management. Its inclusion of faith-based management and Integral human development in the curriculum and co-curricular fora is an excellent springboard to pursue a spiritually-driven management as a business perspective. This is in line with MOD’s tagline: Bridging faith and management practice.

DLSU, like all other Catholic business schools, must renew its understanding of faith and spirituality beyond the bounds of its religious tradition in order to develop a management spirituality that is inclusive of all other spirituality and religiosity (Rahner, 1968; Ebner, 1977; Hudtohan, 2014). Culturally, it should be driven internally by the Maharlikan kalooban (Reyes, 2013; Mercado, 1994; de Mesa, 1987; Enriquez, 1992) an inner consciousness based on a personal reading of the signs of the time and a belief that God still speaks through history (Moran, 1967). Spirituality in this context need not be dictated and compliant to hierarchical and clerical authority (Helmick, 2014). Teaching globalization without addressing the corporate “heart and soul” of the individual deprives them as business students an in-depth perspective on how to deal with the local and global realities of business (Kilmann, 2001; Livermore, 2010).

What is spiritual?

According to Rentschler (2006, p.29), spiritual has at least four major usages; it refers to: 1. to the highest of any developmental and transrational cognition, transpersonal self-identity (Wilber, 1980); 2. a separate developmental line itself like that of Fowler’s (1981) faith development; 3. a state or peak experience (Maslow, 1964) like nature mysticism (Chopra, 1997; Cowley, 2009; York, 2003), mysticism (Johnston, 1970), mystagogy (Rahner, 1972) and mystery present (Ebner, 1977); and 4. a particular attitude or orientation like openness, wisdom or compassion, which can be present at virtually any state or stage (Wilber, 2000).

A spiritually-driven management makes use of any or all of the four usages of Rentschler in addition to the socio-cultural and theological dimensions as foundational concepts of this study. A management that is spiritually-driven means that the manager and corporate leader are powered by a highest level of personal development which is spiritual in fulfilling the management functions of planning, leading, organizing and controlling for relational and productive excellence in the workplace.

What is spirituality?

An open definition of spirituality is “people’s multiform search for meaning interconnecting them with all living beings and to God or Ultimate Reality. Within this definition there is room for differing views, for spiritualities with and without God and for an ethics of dialogue” (European SPES Institute, n.d.).

Dyck and Neubert (2011, p.490) define spirituality as “a state or quality of a heightened sensitivity to one’s human or transcendental spirit.” Western authors use the word ‘meaning’ to imply a transcendent value which directly or indirectly implies spirituality (Tolle, 2005; Ulrich, 2012; Kilmann, 2001; Hicks & Hicks, 2010; Pape, 2014; Craig & Snook, 2014). Warren (2002) is more direct in weaving purpose as meaningful experience of God. Fifty years ago, Van Kaam (1964, p.42) noted that “Ultimate meaning…is grounded in [man] himself, others, and the ultimate Other.”

In 2015, Unilever in London commissioned Authentic Leadership Institute (2014) to design their Purpose Drives Leadership Program 2020, a workshop intended to “make sustainable living commonplace in the UK and Ireland” (Radjou & Prabhu, 2015). Unilever’s 2020 workshop considered purpose as spirituality s crucial to the workforce. Julian (2014) in his book, God is my CEO, cites the faith-work experience of 20 executive leaders. He used the Bible as point of reference in grounding the principles and values of the chief executive officers in America.

According to Aumunn (1985, p.3) Christian spirituality in the Catholic tradition is about “the lives and teachings of men and women who have reached a high degree of sanctity throughout the ages…[that] the perfection of charity can be attained by any Christian in any state of life.” Downey (1997) opines that “Christian spirituality…is the Christian Life itself lived in and through the presence and power of the Holy Spirit. It concerns absolutely every dimension of life, mind and body, intimacy and sexuality, work and leisure, economic accountability and political responsibility, domestic life and civic duty, the rising costs of health care and the plight of the poor and wounded both at home and abroad. Absolutely every dimension of life is to be integrated and transformed by the presence and power of the Holy Spirit.”

From a psycho-spiritual point of view, spirituality considered as wholeness and wholeness is equated to holiness because human and spiritual development is intertwined (Erickson, 1968; Shea, 2004; Caluag, 1980). Friel (n.d.) says, spirituality can be defined as a “fully human phenomenon, and it is a phenomenon of the fully human.”

Geigle’s (2012, pp.18-23) review of related literature on workplace spirituality listed 70 studies from Europe, America, Middle East, Africa and Asia. In Asia, studies from China, India, Taiwan, Thailand, Malaysia, and Sri Langka were mentioned but none from the Philippines. He also reported that Oswick (2009) who compared “the two 10 year periods ending in 1998 and 2008…found the number of books on workplace spirituality increased from 17 to 55 and the journal articles increased from 40 to 192” (Geigle, p.14.)

Karakas’ (2010) reviewed 140 related studies and listed 70 definitions of spirituality at work. He concluded that spirituality provides: 1. a human resource perspective, 2. a philosophical perspective, and 3. an interpersonal perspective that drives organization performance. Spirituality is a driver well-being, sense of meaning and purpose of work, and sense of community and interconnectedness. Spirituality “enhances the general well-being of the employee by increasing their morale, commitment and productivity and by reducing stress, burnt-out and workaholism” (Karakas, p.12). Spirituality “provides employees and managers a deeper sense of meaning and purpose at work” (Karakas, p.16). Spirituality provides a sense of community and connectedness, increasing their attachment, loyalty, and belonging to the organization.

Kouzes and Posner (2003) argue that emotionally, spiritually, and socially barren workplaces can turn around to become abundant workplaces by providing solutions that incorporate spirituality. The ultimate result is spirited workplaces of the 21st century that are engaged with passion, alive with meaning and connected with compassion.

Benefiel, Fry and Geigle (2012, p.184) assert that “Spirituality and religiosity in the workplace (SWR) is an emerging area of scholarly inquiry that has an atypical history in that it has its roots in philosophy and psychology of religion and spirituality.” They likewise cited Mitroff and Denton’s (1999) landmark study where “SRW has begun to experience some convergence, both theoretically and empirically, on the importance of an inner life or spiritual practice in fostering a vision and a set of altruistic values that satisfy fundamental spiritual needs for calling and community, which in turn positively influence important individuals and organizational outcomes.”

A plethora of studies on spirituality in the workplace (SW) and religiosity in the workplace (RW) led me to combine studies on spirituality and religiosity in the workplace (SRW). But Geigle (2012, p.17) observed that “There is little empirical literature concerning mystical/religious constructs many use in their definitions, such as transcendence and interconnection with non-physical entities.” He also cited the following research gap questions: 1. Is it possible to develop spirituality in employees? 2. What is the relationship between secular spirituality and religious spirituality? 3. How can work spirituality constructs differ from related constructs in organization behavior, organization development, and positive psychology?

Employees are spiritual beings

Studies in management have concluded that employees are spiritual and that spiritually-driven leaders (Pruzan & Miller, 2003; Miller & Miller, 2002) make a difference in the workplace. Empirical evidence based on studies on spirituality in the workplace and spirituality-religiosity in the workplace has established that the corporation is manned by spiritual beings, no longer machines of the industrial age, no longer labor for production, and no longer human beings with rights but spiritual beings with human corporate activities.

Maschke, Preziosi and Harrington (2008, p.11) concluded that “spirituality exists in corporations, simply because all employees are spiritual beings.” They affirmed Teilhard de Chardin (1957) who much earlier said that we are not human beings with spiritual activities but spiritual beings with human activities. To De Chardin, the human-spiritual development in Chardin’s view is powered by the same universal laws that are operative in the material world. He wrote, “[E]verything is the sum of the past [and] nothing is comprehensible except through its history. Nature is the equivalent of ‘becoming’, self-creation: this is the view which experience irresistibly leads us…There is nothing, not even the human soul, the highest spiritual manifestation we know of, that does not come within this universal law” (De Chardin, 1920).

That employees are spiritual is a giant leap from a medieval paradigm which declared that only kings are divine and have divine rights. Walsch’s 21st century paradigm considers every human being as divine. The acceptance of employees as spiritual beings forms a basis for a spiritually-driven management.

Further, before Teilhard de Chardin died in 1955, he announced that we are spiritual beings with human activities. Neale Donald Walsch (2014, p.160) courageously announced that “human beings are divine, each having the all the divine qualities within them.” Finally, after more than four decades, he echoes Rahner (1966) and Ebner’s (1977) pronouncement that “All people are divine.”

Related Literature towards a Spiritually-driven Management

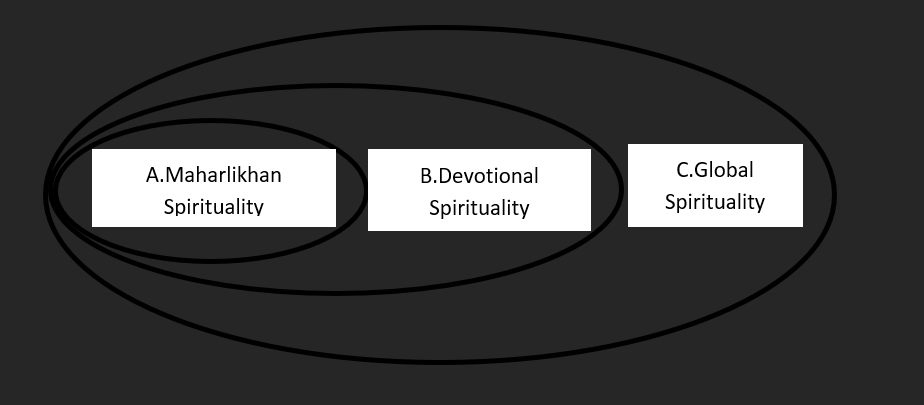

Based on my review of related literature on spirituality, I classified three spiritual tenets that influenced contemporary Catholic believers in the Philippines. These are: A. Maharlikhan spirituality, B. Devotional spirituality and C. global spirituality as shown in a linear, historical development in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Conceptual Framework for Spiritually-driven Management: a linear-historical development of three spiritualities

Maharlikhan spirituality

Maharlikan ethnic spirituality was practiced before 1478 when the islands belonged to the Royal Kingdom of Maharlikha (www.rumormillnews.com/pdfs/The-Untold-Story-Kingdom-of-Maharlik hans.pdf) under the Srivijaya empire that ruled from 683-1286 (Munoz, 2006) and the Majapahit Empire that ruled from 1293-1500 (www.rumormillnew.com/pdf/The-untold-story-of-Maharlikans.pdf). According to the Nagarakretagama (Desawarñana, 1365), the Majapahit empire stretched from Sumatra to New Guinea and it included present day Indonesia, Singapore, Malaysia, Brunei, southern Thailand, Sulu Archipelago, Manila, and East Timor (http://dbpedia.org/resource/ Majapahit).

The Laguna Plate dated 900 AD (Postma, 1992) had an inscription that condoned the debt of the descendants of Namwaran (926.4 grams of gold) which was granted by the chief of Tondo in Manila and the authorities of Paila, Binwangan and Pulilan in Luzon. The words were a mixture of Sanskrit, Old Malay, Old Javanese and Old Tagalog. This establishes the Maharlikan connection with the Srivijaya empire and Majapahit empire.

This is one of the reasons why Philippine national hero, Dr. Jose Rizal, is referred to as “the pride of the Malay race” and “the Great Malayan” (Trillana III, 2014). In fact, Malaysian leader Anwar Ibrahim has recognized Rizal as the “greatest Malayan” and an “Asian Renaissance Man” (Palatino, 2013).

In 1478, the Moslems came to power and in 1521, through Ferdinand Magellan, Spain colonized the island up until 1898. But prior to the Moslem and Spanish conquest, the Maharlikans were ruled by the rajahs and the babaylans were already ministering to the spiritual life of the barangays through song, dance, healing, worship, and metaphysical connectivity with Bathala.

Nona (2013, p.8) in her research, Song of the Babaylans, retrieved and reclaimed “the ancient indigenous sounds that heal, and which have been passed from generation to generation through the present and remaining babaylans – the ritualists, oralists, and healers.” Cacayan (2005) narrated her personal encounters with the babaylans of Mindanao and their sacred tradition of worship and spirituality through dance. She concluded that the spirituality of the babaylan is wholeness.

Velando (2005) reported a babaylan art exhibit at the Kennel’s Center Commuter Art Gallery in New York City. It was noted that the babaylan knows all things; that all people and all existence are connected; and this connection is our ethnic pakikipagkapwa. Villariba (2006) cited the relevance of the babaylans in the 21st century as priestess, healer, sage and seer. According to her, the babaylan lives and breathes the Divine Source because “I Dios egga nittam nganun.” God is in all of us, as found in Mangurug, Ibanag creed and Ba-diw Ibaloi chants. She also cited the role of the babaylan in the context of contemporary justice and peace issues in the Philippines, reminiscent of the participation of the babaylans in Philippine revolution. Melencio (2013) acknowledged them as spiritual and political leadership of the babaylans who, due to Spanish persecution, eventually participated in Philippine revolution.

Vergara (2011) observed that biblical references were used to demonize the babaylans. He cited the derogatory Spanish words that referred to the babaylans as las viejas (old women), sacerdotisas del demonio (demon’s priestesses), hechicheras (sorceresses) and aniteras (priestesses using anito). Veneracion (1998) noted that the Spanish priests instituted the beaterio as a convent haven for Yndias in their effort to suppress and eventually replace the babaylans

Cruz (2002) theorized that the babaylans eventually entered the fold of Christianity and became beatas. Salazar observed, “[T]hese babaylans became part of the colonial society…as church women tasked with organizing and heading processions…who will assist the priests in their services at the altar” (Salazar, 1999, p.19)

Geremia-Lachica (2012) cited the takeover of the Asogs (male babaylans) in Panay. Kobak and Gutierrez (2002) noted in the book of Alcinas (1668) that asog means effeminate and its Bisayan synonyms are bayug or bantut. It also refers to “a man who behaves like a woman and dresses as a woman. Alcina showed that the office of the priest in ancient times was held by the asogs or effeminate men eventually became a male babaylans (Kobak & Gutierrez, 2002, p.489 & p.155).

Alcina’s (1668) Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas describe 17th century Filipino spirituality under the leadership of the babaylans and asogs. Maharlikan culture then was declared non-Christian based on Catholic doctrines. The Jesuit evangelizers attempted to use the word diwata in reference to ‘true God.’ But the political strength of the Dominicans and the Augustinians in early Christianization of the Philippines blocked this early inculturation of Filipino concepts within the Catholic theology and spirituality.

Contemporary Filipinos “are spirit-oriented…[they] have a deep-seated belief in the supernatural and in all kinds of spirits dwelling in individual persons, places and things…Filipinos continue to invoke the spirits in various undertakings.” (Catechism for Filipino Catholics, 2002, p.15).

Filipino theologians, sociologists and anthropologist have done enormous researches in understanding the ABC of indigenous Filipino culture and Catholic paradigm, where A is Maharlikan ethnicity, B is Colonial Catholicism and C is the result of A and B factors. However, C identified in this paper a folk spirituality no longer faithful to dogmatic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church. Filipino theologians tried to retrieve the lost pre-Spanish cultural tradition but they never succeeded in presenting the imago dei of the Maharlikan period. The effort to reconcile culture with Catholic dogmas ended with views that made Catholic theology dominant. Since then, Filipino spirituality has been described as dual Filipino-Christian split-level spirituality (Bulatao, 1966), folk-Catholicism (Belita, 2006), and inculturation of pre-Spanish indigenous values and Catholicism (Ramos, 2015; Reyes, 2013; De Mesa, 2003; Miranda, 1987; Mercado, 1975).

In all these discourses the babaylan spirituality, from the point of view of mainstream Roman Catholicism, was declared pagan. Thus, the 21st imago dei of a Filipino was greatly shaped by an overpowering ecclesiastical hierarchy whose spirituality conforms to the dogma, moral, and worship prescribed by the Roman Catholic Church. For more than 400 years Catholicism has theologically and practically obliterated the Maharlikhan spirituality.

Given the current clerical and authority-centered governance of the Catholic Church (Helmick, 2014), the Mahalikhan spirituality vis-a-vis current devotional Catholic spirituality has a minimal chance to be mainstream, unless the crisis of confidence in the Catholic Church snowballs into a Copernican spiritual revolution (Hicks, 1987).

Devotional spirituality

The Catholic Church in the Philippines and the Catholic Church in Rome have articulated the importance integrating local cultural values with the universal goals of Christianity. The outcome of this glocal initiative is devotional spirituality.

The Catechism for Filipino Catholics (CBCP, 1997, p. 416) quotes the National Catechetical Directory for the Philippines (1984) which declares that the ordinary Filipino Catholic “knows Catholic doctrinal truth and moral values [which] are learned through…devotional practices.” The Second Provincial Council of Manila (1996, p.157) states that lay formation “refers to the particular spirituality of the lay person which needs to be developed …so that he or she might properly fulfill his/her functions. The spirituality to be formed should…seek to respond to the call to holiness (PCP II). The spirituality should have “a distinctly Filipino character…living out of traditional values like pakikipagkapwa-tao, pakikisama, pakikiramdam, utang na loob, lakas ng loob, hiya, bayanihan, etc.” (PCM II).

The Compendium of Social Doctrine of the Church (2004, p.335) states that “The lay faithful are called to cultivate an authentic lay spirituality by which they are reborn as new men and women, both sanctified and sanctifiers, immersed in the mystery of God and inserted in society.” As such, they contribute “to the sanctification of the world, as from within like leaven, by fulfilling their own particular duties. Thus, especially by the witness of their own life…they must manifest Christ to others” (Lumen Gentium, 78)

Devotional spirituality is church-mandated spirituality rooted in the believer’s concept of imago dei (man as image of God) in accordance with her/his religious affiliation to an institutional church. Teloar (2005) in a collection of papers on theological anthropology, reported that the ecclesial traditions of the Orthodox Church view on soteriology (doctrine of salvation) as ‘deification’ where humans participate in the divine fellowship and commune, which is based on creation in the image of God. He concluded that in theological anthropology, salvation is “understood not so much as theosis (deification) but as anthroposis: our becoming more fully and authentically human as our relationships participate in the divine koinonia” (Teloar, 2005, p.3). The World Council of Churches on theological anthropology (Teloar, 2005) in Australia affirmed the humanistic interpretation of God’s salvific action in Christ’s redemptive act which has been espoused for the past four decades (Rahner, 1966, 1968; Endorsain, 1970; Ordonez, 1970; Schleck, 1968; Ebner, 1975 & 1977).

The imago dei in the Philippines was nurtured by the Catholic-Protestant tradition during the colonial period (1521-1946). In 1593, Doctrina Cristiana was published and it became the first manual of hermeneutics that introduced to the Maharlikan culture the fundamentals of religious belief based on Catholic dogma, morals, and worship. The early Jesuit evangelizers attempted to use the word diwata in reference to ‘true God’ but the theological influence of the Dominicans and the Augustinians successfully blocked this inculturation of Filipino concepts within the Catholic theology and spirituality (Alcinas, 1668). Forever lost is the imago dei of the Maharlikhan Bathala who created Malakas and Maganda nestled in the bamboo nodes. Eugenio’s (2001) collection of folkloric literature cites the myth of Maharlikhan creation in Hiligaynon which has parallel versions in other Filipino dialects (Belita, 2006, p.111).

The massive presence of religious orders during the evangelization period brought about distinct Catholic spiritualities based on the founders of the respective religious orders in the Philippines. Thus, we still have the spirituality based on the Augustinians vita apostolica [living alone but in a community] that dates back to the monastic West of 4th century; the Dominicans of the 13th century carried a “doctrinal spirituality and apostolic spirituality” assiduously based on the sacred teachings of the Church; and the Jesuits post-Tridentine devotion moderna spirituality Ignatius of Loyola’s 1548 spiritual exercises (Aumunn, 1985).

Devotional spirituality is founded on a theology of supplication (Walsch, 2014); relying heavily on the intercessory power of a third party that links the supplicant with God. This practice in the Catholic Church is manifested by the statues and images of Jesus, the Blessed Virgin and an array of saints whose special intercessions are invoked through novena prayers, either in private or in community. In particular, Wright (1999, pp. iii-iv) published Lasallian Prayers in a University Setting, making available formula prayers seeking, among others, the intercession of 11 Lasallian saints and blessed for students and teachers in the classroom.

Catholics schools carry the spirituality of their founders: Agustinian La Consolacion College, Benedictine San Beda College and St. Scholastica’s College, Dominican University of Santo Tomas, Ignatian Ateneo de Manila University, Lasallian De La Salle University, Escrivan University of Asia and the Pacific, and Millerettian Assumption College to name a few. Vatican II has mandated the renewal of these religious orders to capture the spirit of the time. But daily, at regular intervals, Catholic schools continue a devotional practice with a short prayer and ends by invoking the name of their respective saint and everyone responds, “Pray for us.” Under the banner of the Catholic Educational Association of the Philippines, devotional spirituality among Catholic schools, colleges and universities is systematically practiced.

Global spirituality

Lynch (2007) introduced a new strain of spirituality called progressive spirituality in the 21st century. He also introduced a variation of pantheism, which traditionally has been identified by the Roman Catholic hierarchy as worship of nature. Pan(en)theism, according to Lynch “promotes sacralization of nature as the site of divine presence and activity in the cosmos – and the sacralization of the self, for the same reasons” (p.11). He rewrites pantheism as pan(en)theism to veer away from worship in nature identified historically with paganism.

He says, “The emphasis on the ineffability of this divine presence leads advocates to progressive spirituality to regard all constructive religious traditions as containing insights that can be valuable for encountering the divine. But at the same time, progressive spirituality is highly critical of aspects of these traditions which are patriarchal and offer a ‘top-down’ notion of a God, separate from the cosmos, who seeks to order human in an authoritative way” (Lynch, p.11).

This commentary of Lynch affirms what Helmick (2014) observed that the root of crisis of confidence in the Catholic Church is due to the stranglehold of clericalism and authoritarianism that control the spiritual life of faithful and the church hierarchy. He asks, “Can we indeed have a Church without this aura of clericalism and authoritarianism?” (Helmick, 2014, p.13). Kellerman (2012, p.73) made a similar observation: “In the last decade, the Catholic Church endured a crisis in confidence. To have witnessed church officials from the pope down, succumb to the demands of the people has been to witness the diminution of political influence.”

The 21st spirituality has been driven by “1. The desire to find new ways of religious thinking and new resources for spiritual growth and well-being that truly connects with people’s beliefs, values and experience in modern, liberal societies. 2. Various initiatives to develop a spirituality that is not bound up with patriarchal beliefs and structures, and which can be relevant and liberating resource for women. 3. Attempts to reconcile religion with contemporary scientific knowledge and in particular in attempts to ground spirituality in a contemporary scientific cosmology, and 4. Moves to develop a spirituality which reflects a healthy understating of the relationship of humanity to the wider natural order and which motivates constructive action to prevent ecological catastrophe ” (Lynch, 2007, pp. 23-35).

Global spirituality is supported theologically by Ebner’s (1977) human race church, Rahner’s (1969) anonymous Christian, Schlette’s (1966) great religion as ordinary way to salvation, McBrien’s (1969) Kingdom of God not the Church as absolute, and Hick’s (1987) Copernican revolution to renounce religious superiority.

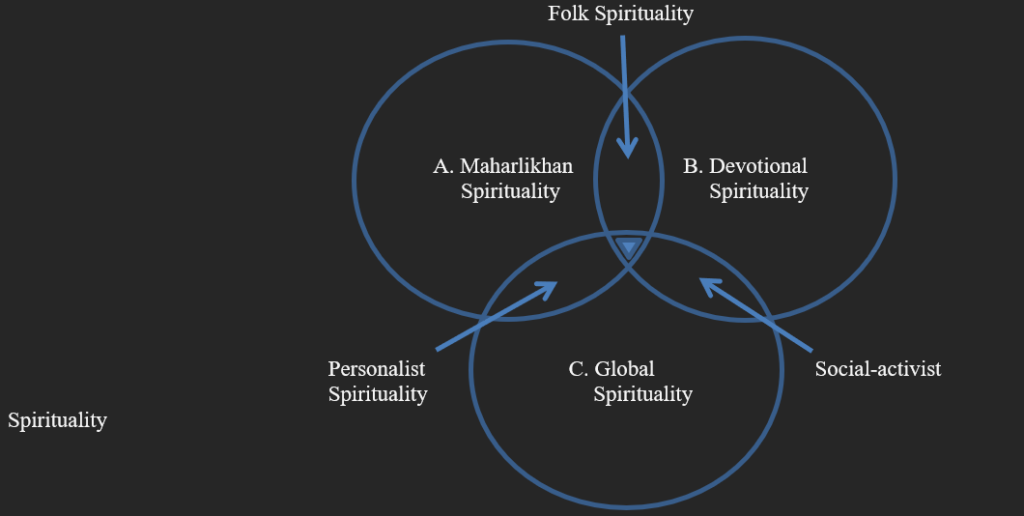

Figure 2. Conceptual Framework for Spiritually-driven Management: a relational convergence of three

Spiritualities. Legend: = vortex of a sustainable spiritually-driven management.

As shown in Figure 2, Maharlikhan spirituality merged with devotional spirituality merged results to a folk spirituality; devotional spirituality with global spirituality becomes asocial-activist spirituality; and Maharlikhan spirituality with global spirituality becomes personalist spirituality. The question of change in one’s spirituality may be viewed in the context creative fidelity (Johnston, 2000). Gonzalez (2002, p.4) supports such fidelity by being “faithful to the traditions of the Catholic Church and at the same time being responsive to the current issues of the time.” On the other hand, Dyer, Gregersen and Christensen (2011) indicate that when creativity is applied to an existing reality, it becomes a disruptive innovation. Spiritual change inevitably includes disruption of existing devotional practices and mainstream beliefs.

Browning (2005) posits that the current state of a person is the result of the interplay between nature (DNA), and nurture (environment) called emergentics. She defines emergenetics as “the constantly emerging combination of genetics and environment…a pattern of thinking and behaving that emerge from your genetic blueprint” (Browning, 2005, p.31). Kragan’s (2003) biological metaphor is simple: A+B=C and C is neither A or B. Figure 2 shows that Maharlikhan spirituality is A; Devotional spirituality is B; and Global spirituality is C. The convergence of the three spiritualities is a vortex of sustainable spiritually-driven management. The convergence of A and B resulted to Folk spirituality; B and C to Social-activist spirituality; and A and C to Personalist spirituality. The creative process of combining the three major spiritualities resulted to another three spiritual variants. In the process, the two basic spiritual elements are disrupted when experiencing a new spiritual mode: folk, personalist and social-activist spirituality

Folk spirituality

Filipino spirituality is founded on folk Catholicism. Sison (2015) describes folk Catholicism as “an attempt to combine contradictory beliefs and melding different schools of thought.” Belita (2006, p.14), making a distinction between folk and popular religion, says, “The word ‘folk’ when put before ‘religion’ is intended to mean the religion of rural folks, more preliterate than literate and the phrase ‘popular religion’ is made to refer to religion that is associated with urban and literate society.” In demonstrating popular religion with popular Catholicism among Filipinos, Belita (2006) narrates Ilonggo spirituality in terms of harmony with nature (tabitabi lang), harmonization with one’s own spirit (dungan), and ginger shamanism (paluy-a).

Folk spirituality is a manifestation of split-level Christianity (Bulatao, 1966); it is inculturated Christianity among Filipino theologians like Ramos (2015), De Mesa (2003) and Mercado (1976). For them, inculturated spirituality is an integration process of interlocking Filipino values and cultural practices with Catholic doctrines and practices.

Split-level spirituality is based on the observation of Bulatao, a psychiatrist-theologian, who described the contemporary Filipino as a split-level Christian. The issue raised is about Catholic doctrines and the application of these principles in real life; the problem of faith and good moral conduct; and the question of being a totally committed Catholic. Inculturated spirituality is based on De Mesa’s (2006) theological appreciation through contextualization, which sees Christianity as a dynamic movement towards inculturation of Catholic teachings with Philippine cultural ethnic values. He is joined by Mercado (1976, 1992) who argued that Christianity must be inculturated through indigenization. Folk spiritual rituals have been observed in fiestas, processions, pilgrimages, novenas, and devotional practices either individually or communally (Ramos, 2015; Eleuterio, 1989).

The problem with folk spirituality, split-level Christianity, and inculturated spirituality is the attempt of theologians to influence the Maharlikhan ethnic culture using Roman Catholic standard of moral, dogma and worship official pronouncements. As Browning and Kagan observed when two elements are mixed, unless one overcomes the other, a new and distinct culture will emerge. In this case the phenomenon of folk, split-level and inculturated spiritualities are new spiritual realities. The reality is that Catholicism continues to dominate the cultural-social-spiritual life of the Filipinos and this has been going on for more than 400 years. This means that the Maharlikan spirituality is almost at a minimal state when the two spheres of influence intersect in Figure 2.

The Second Plenary Council of the Philippines (1992, p.76) acknowledged that “Our history shows both the fruits of inculturation and the sad consequences of its lack…to inculturate both the Church and the Gospel…We have to raise up more and more Filipino evangelizers, formed in a ‘Filipino way.’ We have to develop a catechism and theology that are authentically Filipino, and a liturgy that is truly inculturated. We have to develop ecclesial structures responsive to Filipino needs.”

Social activist spirituality

The combination of Catholic spirituality and contemporary 21st spirituality produced social-activist spirituality. Social activism in the Catholic has shifted from labor-management issues to environment-management concerns because of global warming and climate change. Pope Francis leads in Catholic social activism. He wrote Heaven on Earth in 2013 and issued an apostolic exhortation in Evangelii Gaudium (2013). He underscored the importance of saving God’s creation in the face of climate change in Laudate Si, mi Signore (2015) and connected us to Mother Earth when he said, “The violence present in our hearts…is also reflected in the symptoms of sickness evident in the soil, in the water, in the air and in all forms of life.” Pope Francis is seeking to reverse the effects of global warming and climate change by “reconnecting with the biosphere and harmonizing world industrial activities with nature” (Rockstrom, 2015). He echoes what the pristine babaylans were practicing prior to Western colonization and global industrialization in the Philippines. His leanings toward the poor reflect his own assessment as communist in nature. In his visit at Latin America he said, “I talk about this [land, roof, work], some people think the Pope is a communist…They don’t realize that love for the poor is at the center of the Gospel” (Inquirer, 2015).

For more than a hundred years, the social teachings of the Church addressed the labor-management issues and Marxist-capitalist views related to creation of profits in business: Rerum Novarum (On the condition of labor) of Pope Leo XIII in 1891, Quadragesimo Anno (After 40 years) of Pope Pius XI in 1931, Mater et Magistra (Christianity and Social Progress) of Pope John XXIII 1961, and Centesimus Annus (The Hundredth Year) of Pope John Paul II in 1991.

A number of encyclicals were written to encourage the lay members of the Church to take an active part in changing the social conditions of the oppressed. Populorum Progressio (On Development of Peoples) addressed the development of all people belonging to various religious tenets by Pope Paul VI in 1967. Laboren Excelens (On Human Work) addressed the dignity of labor by Pope John Paul II in1981. Solicitudo Rei Socialis (On Social Concerns) called the attention of Church regarding global poverty and human deprivation by Pope John Paul II in 1987. Gaudium et Spes (Pastoral Constitution of the Church in the Modern World) became a key social doctrine on how the Church should be part of the modern society after Second Vatican Council was held in 1965. The Octogesima Adveniens (A Call to Action) cited the involvement of the laity as pastoral partners by Pope VI in 1971.

The hierarchical mandate and exhortation of the Catholic Church on social issues are voluminous. Rifkin (2003, p.19) says, “Roman Catholic teachings are a distinct blend of doctrines often viewed by outsiders as conservative on lifestyle issues and liberal on social welfare issues.” But as Helnick (2014) observes, the crisis in the Catholic Church today is that of clericalism and authoritarianism. While the pastoral encyclicals and exhortations are trumpeted as directional guidelines and framework for social activism, the Catholic Church to simply doing a pastoral activism. The logic seems to be that the Church hierarchy makes announcements; the Church laity implements the mandate and the invitation to action.

On the ground, the laity has accepted the responsibility passed on to them by the ecclesiastical hierarchy but the Catholic hierarchy and its attendant representatives like the religious orders are not ready to share their power politically, and much more financially, in joining the laity perform the task for concerted action.

Personalist spirituality

The outcome of Maharlikhan spirituality and contemporary 21st century spirituality is a non-denominational spirituality, no longer founded on church-based or religion-based spirituality. This spirituality according to Ebner (1977) is founded on contemporary theology which is both personalist and existentialist. It is personalist because it relies on self-revelation in contrast to Church-based revelation regarding theological dogma and truth, and existentialist because it addresses the current experience of the believer.

The theology of application, in contrast to Catholic theology of supplication, encourages that “we apply in our lives what we know to be true about our relationship to God, that God lives in us, through us, as us, and that the qualities of divinity are ours to apply in our daily lives, including wisdom, clarity, knowledge, creativity, power, abundance, compassion, patience, understanding, needlessness, peace and love” (Walsch, 2014, p.90).

Two Filipino personalist non-denominational spiritual advocates: George Sison (2009) and Tato Malay (2014). They are also metaphysical-spiritual writers whom I consider as modern asogs, male babaylans (Alcinas, 1668) of our ethnic past and modern urban shamans (Samuels & Lane, (2003).. They profess the innate power of human nature in the tradition of Page (2008), Edwards (1999, 1997), Walsch (2014), Bushnell (2005), Ferguson (2010), Boorstein (2007, 1997), Nemeth (1999), Vitale (2007), Day (2007) and Ohana (2005) who advocate the relevance of consciousness in the 21st century in the fashion of Grabhorn (1992, 2004), Williamson (2008), Dyer and Hicks (2014) and Hicks and Hicks (2010).

In Ebner’s (1977) paradigm, a non-denominational spirituality is a personalist-existentialist expression of God present as mystery. His Human Race Church embraces all beliefs and faith traditions, and here I must say, the Maharlikan spirituality is included “For not all men, presumably, are called to be Christians or Buddhists, but all men are called to be Godians and mysterians. He explains mystagogy as “the approach of the missionary who goes not to benighted pagans but to people already in touch with the divine” (Ebner, 1977, p.44). Rahner’s (1972) mystagogy reaffirms the pristine value of Maharlikhan spirituality whose God is Bathala. Walsch explains this new spirituality as “simple but startling acknowledgement that our Ancient Cultural Story contained so many inaccuracies…Might it be that God who is continuing to send us the Original Message, and continuing to invite us to hear it and receive it over and over again through the millennia, each time with new and maturing ears?” (Walsch, 2014, p.18)

Sison (2009), as an asog, advocates reinventing one-self. In more ways than one, he is teaching his readers to become a babaylan or asog, whose power to perform miracles come from a realization of that power from within which is a gift from Above. He says, “Fine tune your imagination…get rid of your dislikes,” which Hicks and Hicks (2008) and Walsch (2014) likewise proclaim that we must state and claim our preference. His discussion on Have Your Ways of Reaching Out says that giving advice is really adding vice. Therefore give alternatives, but don’t add vice because miracles of healing come from within. His discussion on Acclimatize Yourself to Affluence is akin to Hicks’ teaching that desires have a frequency and vibration. He recommends moving towards the frequency of our dreams. And finally, his discussion on Reawaken to the Truth is a celebration of our divinity, because the truth that “You are God as you.” will set you free as you meditate on “I am becoming me.”

Malay (2014) is a reincarnation of an asog of Maharlikhan tradition. From his book, Lessons I Never Learned in School, his chapter on Universal Laws of Success summarizes 21st century spirituality discussed by Neale Donald Walsch; he reechoes the teachings of Sison that God is within us. He explains in a more doable way the teachings of Beck (2012) and Esther Hicks and Jerry Hicks (2010) on how to manifest desires and it illustrates in a practical way the universal laws as explained in Real Energy by Phaedra and Isaac Bonewits (2007).

The chapter on I am Kamalayan ends with a personal truth, rather than a mere truism: What one can conceive, one can create. He knows very well how he can make this world a reality. He says, “A kamalayan learner believes that one’s level of consciousness is the power that creates one’s reality.” (Malay, 2014, p.36). Like a guro and guru for and of the 21st century spirituality, he mentors people to reconsider their beliefs. He says, “If what you are experiencing now is not exactly favorable, examine your beliefs and you’ll get an idea where it is coming from and why it is there. Why are you not achieving and living your dreams?” (Malay, 2014, p.92).

Inside the vortex

The vortex of a spiritually-driven management is the convergence of all the six variants of spirituality. According to Hicks and Hicks (2010) inside that vortex is the vibration of energy of life itself, defining Who We Really Are. Getting into the vortex “means focusing your mind upon the thoughts that allow your alignment with the broader part of who-you-really-are. And who you really are…is already in the Vortex” (Hicks & Hicks, 2010, p.xii).

Inside the vortex is “vibrational energy [that] can resonate within you about your essence, about finding yourself in the deepest level” (Samuels & Lane, 2003, p.18). Walsch asserts “In the moment that we accept that we are, each of us, individuated expression of The Divine, we realize as well that nothing can happen to us, and that everything must be happening through us…but at our mutual spiritual behest…we might collectively create and encounter conditions allowing us to announce and declare, express and fulfill, experience and become Who We Really Are. It is in this condition that God is made flesh and dwells among us” (Walsch, 2014, p.123).

According to Pillans (2014, p.11), “Wellbeing is comprised of the mutually supportive relationship between the physical, psychological and social health of the individual.” But Dyck and Neubert (2011), Karakas (2010) and Robert, Young and Kelley (2006) refer to wellbeing as a dimension of work spirituality. On the other hand, Hicks and Hicks (2008, p.311) define well-being as “The universal state of feeling good.” They go on to explain it, metaphysically and spiritually, that “The basis of All-That-Is is Well-Being. There is no source of anything that is other and Well-Being. If you believe you are experiencing something other than Well-Being, it is only because you have somehow chosen a perspective that is temporarily holding you out of reach of the natural Well-Being that flows” (Hicks & Hicks, 2008, p.307).

The babaylans and saints have discovered this vortex long time ago but their art of true living has been obscured in modern society. . Ancient wisdom describes the vortex in the words of Walsh (2007) as “The kingdom of heaven is within you.” in Christianity; “Those who know themselves know their Lord.” in Islam; “Those who know completely their own nature, know heaven.” in Confucianism; “He is in all, and all is in Him.” in Judaism; “In the depths of the soul, one sees the Divine, the One.” in The Book of Change; “Atnan [individual consciousness] and Brahman [universal consciousness] are one.” in Hinduism; and “Look within, you are the Buddha.” in Buddhism.

Inside the vortex is a higher state of spiritual life and energy “known by many names: enlightenment, liberation, salvation and satori, fana and nirvana, awakening and Ruah Ha-qodesh, Different names, but all point to the highest human possibility, which, paradoxically is simply a recognition of who we really are” (Walsh, 2007, p.28)

Conclusion

In 1911, the pioneering Brothers came to the Philippines and opened a residencia for the Brothers and school boys and an escuela. Their mission was simple: Christian education of Filipino youth. From that mission, they granted a diploma for a course in business and later a diploma in liberal arts. Historically, the Brothers had kept a human touch in business. As it is today, DLSU has Liberal Arts-Commerce double degree, humanizing business as it were.

Spiritual formation

The call to provide a Christian life among the students did not end in the De La Salle classroom. Spiritual development was further developed in co-curricular organizations of the Sodality of Mary and Student Catholic Action. They served as an evangelization arm of the Church and at the same time a modality for personal spiritual formation. After Vatican II and after the EDSA revolution, the COSCA was born in response to local social needs. As it is today, COSCA leads DLSU in community engagements.

The spiritual pendulum swung from a personal spiritual concern to a social concern driven by corporate social responsibility and Catholic social teachings. The emphasis on individual spirituality has been momentarily interrupted. The proposal for a spiritually-driven management for MOD is an attempt to redirect its focus on the original mission of the Brothers: Spirituality in the 21st century must go beyond faith-based management because of globalization and technological connectedness. Most critical is the the challenge is to rediscover our pre-Spanish consciousness in the pristine Royal Kingdom of Maharlikha in Southeast Asia.

Spiritually-driven management Spiritually-driven management is relocating oneself at the vortex of the three spirituality spheres in conceptual framework Figure 2: Maharlikhan spiritual DNA, Catholic devotional spirituality, and Global 21st century spirituality. Operating from that vortex, one is able to recognize experiences as a result of the convergence of these spiritual phenomena: folk practices (Maharlikhan DNA-devotional spirituality), social-activism (devotional-global spirituality), and personalist spirituality (Marhalikhan DNA-global spirituality).

Sustainable spiritual management An educational leader who is immersed at the vortex of a spiritually-driven management can develop for herself/himself a sustainable new spirituality by applying the situational leadership matrix of Hersey and Blanchard (1988). Leadership in a Catholic institution should recognize that a spiritually-driven manager deals with three spiritual modalities with three spiritual variants. As these six elements of spirituality are personally nurture, a spiritually-driven management at the institutional level would have truly embraced a local and global spiritual environment.

Recommendation

For the De La Salle MOD, the spiritually-driven management framework can be used in redesigning its business curriculum in coordination with COSCA’s co-curricular activities for community engagements. First, using the spiritually-driven framework, MOD’s current programs in “bridging faith and management practice” may be reviewed and studied to provide an empirical data on the strength and opportunities of MOD as a spiritual agent in business management. Second, COSCA may review its role in promoting a social-activist spirituality in coordination with all the stakeholders its serves within the university. Finally, the De La Salle Campus Ministry may wish to promote Maharlikhan spirituality, social-activist spirituality and global spirituality among the students, faculty, non-teaching staff and administrators going beyond its current focus on Lasallian spiritual formation and services.

References

Acts and Decrees of the Second Provincial Council of Manila (PCM II). (1997). Manila: Secretariat Second

Provincial Council of Manila, The Roman Catholic Archbishop of Manila.

Acts and Decrees of the Second Plenary Council of the Philippines (PCP II). (1992). Pasay City: Pauline Publishing

House.

Alcinas, I. F. (1668). Historia de las islas e indios de Bisayas…1668 (C.J., Kobak, C.J. & L. Gutierrez, eds., trans.,

& anno.) published in 2002. History of the Bisayan People in the Philippine Islands: Evangelization and culture at the contact period. Manila, Philippines: UST Publishing House.

Asean University Network Quality Assurance. (2011). Bangkok: Chulalongkorn University.

Ashmos, D. & Duchon, D. (2000). Spirituality at Work: A Conceptualization and measure. Journal of Management

Inquiry, 9(2), 134-145. http://doi.org/10.1177105649260092008.

Aumann, J. (1985). Christian spirituality in the catholic tradition. (Reprint). Broadway, OR: Wipf and Stock

Publishers.

Authentic Leadership Institute. (2015). UK & Ireland purpose drive leadership program 2020. ALI 2014

www.authleadership.com

Baldwin, E. (1982). The spiritual quest on campus: religious practice at De La Salle University, Dialogue,

17. (Special Issue). Manila: DLSU Press, 52.

Banayad, S.J., L.F. (2000). A second look at the apostolate of catechizing. Manila: Excel Publishing Services, Inc.

Beck, M. (2012). Finding your way in a wild new world. New York: Free Press.

Beck, M.. (2008). Steering by starlight. New York, NY: Rondale Inc.

Belita, J. (c.2010). Value-driven: Grounding of morals in evolutionary and religious narrations.

Unpublished paper. Manila: San Juan de Dios Educational Foundation, Inc.

Belita, J.. (2006). God is not in the wind. Ermita, Manila: Adamson University Press.

Benefiel, M., Fry, L. and Geigle, D. (2014). Spirituality and Religion in the Workplace: History, Theory,

and Research. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 6(3), 175-187.

Bloch, M. (1962). The Historian and His Craft. Trans. Peter Putnam. NY: Alfred A. Knop..

Bonewits, P. & Bonewits, I. (). Real energy: Systems, spirits, and substances to heal, change and grow. New Jersey:

New Page Books.

Boorstein, S. (1997). That’s funny, you don’t look Buddhist. New York: HyperOne.

Boorstein, S. (2007). Happiness is an inside job. New York: Ballantine Books.

Braden, G. (2009). Fractal time. California: Hay House, Inc.

Braden, G. (2007) The divine matri. California: Hay House, Inc.

Braden, G. (2008) The spontaneous healing of belief. California: Hay House, Inc.

Brinckerhoff, P. (1999). Faith-based management. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Brown, B.C. (2012). Daring great: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent and

lead. New York: Gotham Books.

Brown, K. and Keats, R. (2003). Citizen-community engagement: community connection through network

arrangement. Asian Journal of Pacific Public Administration,. 107-132.

Browning, G. (2005). Emergenetics: Tap into the science of success. New York: Collins.

Bulatao, J. (1966). Split-level Christianity. Manila: Ateneo University Press.

Bushnell, L. (2005). Life Magic. New York, NY: Hyperion.

Byrne, R. (2006). The secret. New York, NY: Astra Books.

Caluag, J. C. (1972). Teachers’ evaluation of the human evocative approach. De La Salle Manila, Grade School.

Caluag, J.C. (1900). Humanization and Christianization in the Five De La Salle Schools in the Philippines.

University of Sto. Tomas, Manila. Unpublished doctoral dissertation,

Caluag, J.C. (1972). Parent Survey on Attitudes and Values of their Children. Manila: De La Salle Grade School.

Caluag, J.C.(1970). Survey on Attitudes and Values of Grade VI Boys. Manila: De La Salle Grade School.

Carillo, J. (1976). The Human evocative approach to religious teaching: A presentation of its conceptual

framework and an evaluation of its acceptability to selected group of De La Salle grade school students. Unpublished master’s thesis, De La Salle University, Manila.

Carroll, A. B. (1999), Corporate Social Responsibility. Business and Society, 38(3).

Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippines. (2002). Catechism for Filipino Catholics. Intramuros, Manila:

ECCE; Makati: Word & Life Foundation.

Chopra, D. (1997). The seven spiritual laws of success. London: Bantam.

Cowley, V. (2000). Wicca as a mystery religion. In C. Harvey and C. Hardman. Pagan pathways: An introduction

to the ancient traditions. London: HarperCollins.

Clarke, T.E. (1970). Theology. America, 122(1), 25.

Common Rules and Constitution of the Brothers of the Christian Schools.

Craig, N. & Snook, S. (May 2014). From Purpose to Impact: Figure out your passion and put it to work.

Harvard Business Review.

Cruz, R. (2002). Devotion and Defiance. In A.C Kwantes,. (Ed.), Chapters in the Philippine church history.

Mandaluyong City: OMF Literature, Inc., 33-71.

Day, L. (2007). Welcome to your crisist. New York: Little Brow and Company.

De Chardin, T. (1957). Le milieu divine. Harper Perennial 2001 edition.

De Chardin, T. (1920). The Future of Mankind. Published by Harper & Row, New York and Evanston,

1959. http://www.religion-online.org/showchapter.asp?title=2287&C=2162

De La Salle University (2003). Vision, Mission (7th edition). http:/www.dlsu.edu.ph/inside/vision_mission.asp.

De Mesa, J. (1987). In Solidarity with the Culture: Studies in Theological Re-Rooting. Quezon City: Maryhill

School of Theology.

De Mesa, J. (2006). A hermeneutics of appreciation approach and methodology. MST Review, 2.

De Pape, B. (2014). The power of the hear. London: Simon & Schuster UK Ltd.

Doctrina Christiana. (1593). Manila: Orden de Santo Domingo.

Downey M. (1997). Understanding Christian spirituality. New York. Paulist Press.

Dyck, B. & Neubert, M. (2012). Management. Singapore: Cengage Learning Asia Pte. Ltd.

Dyer, W. & Hicks, E. (2014). Co-creating at its best: A conversation between master teachers. London:

Hay House UK Ltd.

Dyer, J., Gregersen, H., and Christensen, C.M. (2011). The innovator’s five skills disruptive innovation DNA

Boston, Massachusetts: Harvard Business Review Publication.

Ebner, J. (1977). God as mystery present. Winona: St. Mary’s College Press.

Ebner, J. (February 13, 1975). New Theology. National Catholic Reporter.

Edwards, G. (1997). Stepping into the magic. Great Britain: Mackys Chatham.

Edwards. G. (1997). Living magically: A new vision of reality. London: Piatkus Publication, Ltd.

Eleuterio, F. (1989). Pre-Magellanic religious elements in contemporary Filipino culture. Manila: De La Salle

University Press.

El Sawy, O.A. (1983). Temporal perspective and managerial attention: A study of chief executive strategic

behavior. Doctoral dissertation, Stanford University cited in Kouzes, J.M. and Posner, B.Z. (1995). The leadership challenge: How to keep getting extraordinary things done in organizations. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass Publishers, 106.

Endorzain, L. (1970). The evolution of catechetics 1959-1968. Theology Digest, 18(3).

Enriquez, V. (1992). From colonial to liberation psychology. Quezon City: The University of the Philippines Press

Erikson E. H. (1968). Identity Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton.

Eugenio, D. (2001). Philippine folk literature. Diliman, Quezon City: University of the Philippines Press.

European SPES Institute. (n.d.). Our Mission: Spiritual-based Humanism.

http://www.eurospes.org/content/our-mission-spiritual-based-humanism#sthash.KsNeEtAu.dpuf

Ferguson, G. (2010). Natural wakefulness: Discovering the wisdom we were born with. Boston: Shambhala.

Geigle, D. (Dec. 2012). Workplace Spirituality Empirical Research: a Literature Review. Business Management

Review, 2(10), 14-27.

Fallarme, C. (1983). The Integration of moral values in the social studies program of PWU-JASMS using the

human evocative approach. Unpublished master’s thesis, De La Salle University, Manila.

Ferguson, G. (2010). Natural wakefulness: Discover the wisdom we were born with. Boston: Shambhala.

Fowler, J. E. (1981). Stages of Faith. New York, NY Harper and Collins, 75-76.

Francis. (2013). Heaven on earth. New York: Image.

Francis. (2013). Evangelii Gaudium. Pasay City, Philippines: Pauline Publishing, Inc.

Friel, J. (n.d.). Reflection on Psycho-Spiritual Development, Daneo Human and Spiritual Development Services,

683, Crumlin Road, Belfast, North Ireland. http://daneoservices.weebly.com/refection-on-psycho-spiritual- development-john-friel-cp.html

Geigle, D. (December 2012). Workplace spirituality empirical research: a literature review. Business and

Management Review, 2(10), 14-27.

Geremia-Lachica, M. (2012). Panay’s Babaylan: The Male Takeover. Review of Women’s Studies, 55.

Gonzalez, A., Luz, J. M., & Tirol, M.H. (1984). De La Salle mission statement:197: Retrospect and prospect.

Quezon City: Vera Reyes, Inc.

Gonzalez, A. (2002). Towards an Adult Faith. Manila: De La Salle University Press.

Gonzalez, A. (2006). God talk : Renewing language about God in the Roman Catholic tradition. Manila:

De La Salle University Press.

Grabhorn, L. (2004). Excuse me, your life is showing: The astonishing power of positive feelings. Great Britain:

Hodder and Stoughton.

Grabhorn, L. 1992). Beyond the twelve steps. Charlottesville, VA: Hampton Roads Publishing Company, Inc.

Gutierrez, G. (1973), A theology of liberation. New York: Orbis Books (Maryknoll, New York),

Haught, J. F. (2000). God after Darwin: Anthology of Evolution. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Heitink, G. (1999). Practical theology: History, theory, action domains: manual for practical theology.

Grand Rapids, Michigan: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing.

Helmick, R.G. (2014). The crisis of confidence in the Catholic Church. London: Bloomsbury T&T Clark.

Hernandez, J.M. (c1960). Catholic action marches On: A decade of Catholic action 1950-

1960. Manila: The National Central Committee Catholic Action of the Philippines,61.

Hersey, P. & Blanchard, K. (1988). Management and organizational behavior. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Hess. D., Rogovsky, N., & Dunfee, T.W. (2002). The Next Wave of Corporate Community Involvement:

Corporate Social Initiatives. California Management Review. 44(2).

Hicks, E . & Hicks, J. (2010). Getting into the vortex. USA: Hay House, Inc.

Hicks, E. & Hicks, J. (2008). Ask and it is given. London: Hay House, Inc.

Hick, J. (1987). The Non-Absoluteness of Christianity. In The myth of Christian uniqueness: Toward a pluralistic

theology of religion. John Hick and Paul F. Knitter (Eds.). Maryknoll, NY: Orbis.

http://dbpedia.org/resource/Majapahit.

Hudtohan, E.T. (May-Dec. 2014). Spirituality in the workplace: Quo Vadis? The Journal of Business

Research and Development. San Beda College Graduate School of Business.

Hudtohan, E.T. (2005). Fifty Years of De La Salle Catechetical Program: Retrospect and Prospect (1952-

2002). Unpublished doctoral dissertation. De La Salle University, Manila.

Hudtohan, E.T. (October 28, 2013). Service to the nation. Manila Standard Today.

Hudtohan, E.T. (August 25, 2014). Youthful exuberance. Manila Standard Today.

Hudtohan, E.T. ( April 15, 1976). Religious Education among De La Salle Schools in the Philippines. A paper

delivered at the Education Day of the De La Salle Brothers. Tagaytay City, Metro Manila.

Hudtohan, E.T, (March, 1972). The Human Evocative Approach: Basis for Integration of Religion and Guidance in

the Grade School. Unpublished masteral thesis, De La Salle University, Manila.

Israel, T. (n.d.). The Untold Story Kingdom of the Maharlikans.

http://www.scribd.com/doc/55070574/The-Untold-Story-Kingdom-of-Maharlikhans#scribd

John XXIII. (1961). Encyclical letter Mater et Magistra.

John Paul II. (1991). Encyclical letter Centesimus Annus.

John Paul II. (1988). Encyclical Letter Sollicitudo Rei Socialis.

John Paul II. (1981). Encyclical Letter Laborem Exercend.

Johnston, J. (2000). The Challenge: live today our founding story, a pastoral letter of Br. John Johnston, FSC,

Superior General of the Brothers of the Christian Schools, excerpts printed in Botana, FSC, A. (2003). The ongoing story, MEL Bulletin 2, Trans. Aidan Maron, FSC. Via Aurelia 476, Rome, Italy.

Johnston, W. (1970). The still point. New York: Fordham University Press, 25.

Julian, L. (2014). God is my CEO: Following God’s principles in a bottom-line world. Avon, MA: Adams Media.

Karakas, K. (2010). Spirituality and organization performance: a literature review. Journal of Business

Ethics, 94(1), 89-106.

Kellerman, B. (2012), The end of leadership. New York: HyperCollins Publishers, 73.

Kilmann, R.H. (2001). Quantum organization: A new paradigm for achieving organizational success and

personal meaning. Palo Alto, CA: Davis-Black Publishing.

Konz, G. & Ryan, F. (1999). Maintaining an Organizational Spirituality: No easy task. Journal of Organizational

Change Management, 12(3), 200-210. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/02683940210423060/.

Kouzes, J.M. and Posner, B.C. (1995). The leadership challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bas.

Kagan, J. (2003). Biology, Context, and Developmental Inquiry. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 54, 1–23.

Livermore, D. (2010). Leading with cultural intelligence. New York: AMACOM, Division of American

Management Association.

Lumen Gentium. (November 21, 1964). Vatican Council II. Flannery, A. (Ed). (2001). 7th printing. Pasay City:

Paulines Publishing House, 394-395,

Lynch, G. (2007). The new spirituality: An introduction to progressive belief in the twenty-first century.

New York: I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd.

Malay, T. (2014). Lessons I never learned in school. Makati City: Temple of Prayer, Peace and Prosperity.

Maschke, E., Preziosi, R. & Harrington, W. (October 2, 2008). Professionals and Executives Support a Relationship

Between Organizational Commitment and Spirituality in the Workplace. Paper submitted to the International Business and Economic Research (IBER) Conference, Las Vegas, NV. September 29 – October 2, 2008.

Maslow, A. (1964). Religions, values and peak experiences. New York: Penguin Books.